WEBLOG

Previous Month | RSS/XML | Current | Next Month

February 23rd, 2012 (Permalink)

Fact-Checking Wikipedia

Historian Timothy Messer-Kruse has an important article in The Chronicle of Higher Education on difficulties he had fact-checking Wikipedia:

The bomb thrown during an anarchist rally in Chicago sparked America's first Red Scare… Its Wikipedia entry is detailed and elaborate. A couple of years ago, on a slow day at the office, I decided to experiment with editing one particularly misleading assertion chiseled into the Wikipedia article. The description of the trial stated, "The prosecution[…]did not offer evidence connecting any of the defendants with the bombing. …" … I have not resolved all the mysteries that surround the bombing, but I have dug deeply enough to be sure that the claim that the trial was bereft of evidence is flatly wrong.

According to Messer-Kruse, when he tried to fix this error, his changes were quickly removed and he kept getting the runaround. Initially, Messer-Kruse cited primary sources as the basis for the correction―which is good historical practice―but this was rejected on the grounds that Wikipedia is based on secondary sources. Two years later (!), after publishing a book on the event―a secondary source―the correction was again rejected on the grounds that the book was just one secondary source, whereas what was required was a consensus of secondary sources. The end result of this policy, of course, is that common errors cannot be corrected. Messer-Kruse would have to wait until his correction had spread through a critical mass of secondary literature before it's ready for Wikipedia.

There is a real problem of how to deal with common errors in the scholarly literature, which is related to the problems of appealing to expert opinion (see the entry for the fallacy of appeal to misleading authority). However, this is not that kind of a problem, since the change that Messer-Kruse made was a matter of fact-checking. Whether the prosecution in a trial offered evidence linking a defendant to the crime is a question that anyone with access to the trial records should be able to answer, that is, you don't need to be an historian to do so. Of course, whether any such evidence was credible, whether it was sufficient to establish guilt, or whether the defendant actually committed the crime, are more controversial issues. Thus, the Wikipedians' insistence that they had to wait for the consensus of historians to change before they could fix this mistake was absurd.

Incidentally, while researching this entry, I noticed that Wikipedia's article on logical fallacies lists a "Wikipedian fallacy":

Simply stating, "It's on Wikipedia, so it must be true." Problem: Not only is Wikipedia edited by the general public, many of whom do not fully know what they are doing, but dogmatically accepting any one source on an empirical matter is often ill-advised.

Messer-Kruse's experience is a good example of why this is indeed a mistake.

Sources:

- Timothy Messer-Kruse, "The 'Undue Weight' of Truth on Wikipedia", The Chronicle Review, 2/12/2012

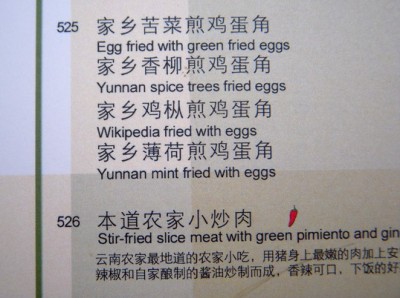

- Funny sign, Funny Signs

Resources:

- A Contextomy and a Contradiction, 2/10/2005

- More Wikipedia Illogic, 4/30/2005

- Wikipedia Watch, 6/30/2008

- Wikipedia Watch, 10/22/2008

- Wikipedia Watch, 1/25/2009

- Wikipedia Watch, 3/22/2009

- Wikipedia Watch, 7/21/2009

February 17th, 2012 (Permalink)

How many errors are there in this puzzle?

Here's a correction from today's Slate:

In the Feb. 15 "Books," Dan Kois admitted the piece had 30 falsehoods. Actually, it has 32. The version of John D’Agata’s essay in The Lifespan of a Fact is different from the one that ran in the Believer.

Apparently, one of the two additional falsehoods was the claim that the essay was the same in the two sources, which meant that there were at least 31 errors in the piece. However, since the piece itself claimed that there were only 30 falsehoods, that made for one more falsehood, bringing the total to 32. This reminded me of the following puzzle:

There is three errers in this sentence.

How many errors are there in this sentence?

Sources:

- "Corrections", Slate, 2/7/2012

- Funny sign, Funny Signs

February 15th, 2012 (Permalink)

Be your own fact checker!

Get out your used cocktail napkins, because it's that time again: time to play "plausibility check"! Being able to test factual claims for plausibility is a very useful critical thinking skill and, unfortunately, one that is usually neglected in textbooks and classes.

Consider the following claim from an online article on eating disorders: "nearly 150,000 women in the U.S. die from anorexia every year". Is that a plausible number?

Don't just assume that because you read it on the internet it must be true. Check it for plausibility. How can you check a factual claim's plausibility? I'm not talking about doing research, but about the step that comes before that. Unless you're a factchecker for a publication or publisher, you won't have the time or energy to check every factual claim that you come across, but that doesn't mean that you should just swallow whole every claim that someone makes―at least, not if you're a critical thinker. Here's a chance for you to practice.

How do you do it? You already know lots of things, so make use of what you know. Compare the claim to other things that you know. A "back-of-the-envelope" calculation (BOTEC) may be of help (see the Previous Weblog Entries, below, for more on BOTECs). So, grab some junk mail and start checking!

Source: Linda Nielsen , "Black Undergraduate And White Undergraduate Eating Disorders And Related Attitudes", Healthy Place, 12/7/2011

Previous Weblog Entries:

- Caveat Lector, 6/25/2007

- The Back of the Envelope, 5/29/2008

- Who is Homeless?, 3/30/2009

- The Back of the Envelope, 7/2/2009

- The Back of the Envelope, 8/15/2009

- BOTEC, 11/14/2010

- How Not to Do a "Back of the Envelope" Calculation, 11/18/2010

- BOTEC, 2/6/2011

- Go Figure!, 3/6/2011

February 3rd, 2012 (Permalink)

Blurb Watch: Man on a Ledge

The new movie Man on a Ledge has had some trouble with the critics: its Metacritic Metascore is 40 out of 100, which technically means "Mixed or Average Reviews", but one point less and it would be "Generally Unfavorable Reviews". Similarly, it scores a rotten 32% on Rotten Tomatoes' Tomatometer. So, what's an adwriter to do for a blurb? Contextomy to the rescue! An ad for the movie has the following blurb:

"TAUT AND SUSPENSEFUL."

Elizabeth Weitzman, NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Based on that quote, you might think that Weitzman at least liked the movie, even if few other critics agreed with her. However, the context gives a different impression:

“You gotta love New York,” says a stock character in Asger Leth’s stolidly literal-minded “Man on a Ledge.” But New Yorkers are probably too sharp to fall for this movie’s obvious ploys. While Leth does work hard to inject some local character into his tense thriller, the stars and setup are pure Hollywood. An incongruously gorgeous Elizabeth Banks plays down-and-out Detective Mercer, who’s ordered to midtown’s Roosevelt Hotel on an apparent suicide call. The man on the ledge is Nick Cassidy (stiff Sam Worthington), himself a former NYPD officer. … Screenwriter Pablo Fenjves start [sic] with a promising premise, and the opening scenes are taut and suspenseful. A late-day chase scene picks up the sagging middle, but Leth totally fumbles what should be the movie’s biggest moment. The primary problem is that he seems to want things both ways, seeking gritty, socially relevant New York realism from an unconvincingly glam cast…saddled with hokey dialogue. … Like Cassidy, Leth never quite knows whether to jump or stand firm. Too often, he just winds up wobbling in the wind.

This is a case of the oldest trick in the book of blurbs, namely, quoting praise of a part or aspect as if it applied to the whole.

Sources:

- Ad for Man on a Ledge, The New York Times, 2/3/2012, p. C19

- Elizabeth Weitzman, "‘Man on a Ledge’ with Sam Worthington fumbles try at New York cop thriller", New York Daily News, 1/26/2012

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Funny Signs for the funny sign.

The Back of the Envelope: There's not just one way to test a factual claim for plausibility, and how you do so will depend upon what you happen to know. One way to do so is to compare the claim about something you don't know with something similar that you do know, which can help put the claim into perspective.

For instance, you may know that the number of Americans killed in automobile accidents in a year is around 50,000―more precisely, according to Wolfram Alpha, a little over 43,000 fatalities were estimated for 2005―which would mean that over three times as many women die of anorexia as people of both sexes are killed in car accidents. Is that plausible? Wouldn't anorexia be a much bigger deal if that were the case, and wouldn't we hear a lot more about it?

This, in fact, was the approach taken by philosopher Christina Hoff Sommers, who seems to have been the first to debunk this claim. In her book Who Stole Feminism? she wrote:

In Revolution from Within, Gloria Steinem informs her readers that "in this country alone…about 150,000 females die of anorexia each year." That is more than three times the annual number of fatalities from car accidents for the total population.

Alternatively, you might know that around 60,000 American soldiers were killed during the Vietnam war, which occurred over the course of several years. In other words, the 150,000 figure would be the equivalent of two-and-a-half Vietnam wars occurring every year, but killing young American women instead of young American men. Is that plausible?

Also, if you know that anorexia is a disease that strikes primarily young women and girls, you may realize that 150,000 is a huge number of deaths in a single year. Because they tend to be healthy, the most common causes of death for young people are accidents and violence rather than disease. This approach was used by Joel Best in his book Damned Lies and Statistics:

Consider one widely circulated statistic about the dangers of anorexia nervosa…. At some point, feminists began reporting that each year 150,000 women died from anorexia. … Yet it should have been obvious that something was wrong with this figure. Anorexia typically affects young women. In the United States each year, roughly 8,500 females aged 15-24 die from all causes; another 47,000 women aged 25-44 also die. What were the chances, then, that there could be 150,000 deaths from anorexia each year? But, of course, most of us have no idea how many young women die each year ("It must be a lot…."). When we hear that anorexia kills 150,000 young women per year, we assume that whoever cites the number must know that it is true.

Author Naomi Wolf came close to checking the claim for plausibility, but drew the wrong conclusion:

Each year, according to the [American Anorexia and Bulimia] association, 150,000 American women die of anorexia. If so, every twelve months there are 17,024 more deaths in the United States alone than the total number of deaths from AIDS tabulated by the World Health Organization in 177 countries and territories from the beginning of the epidemic until the end of 1988; if so, more die of anorexia in the United States each year than died in ten years of civil war in Beirut. Beirut has long been front-page news. As criminally neglectful as media coverage of the AIDS epidemic has been, it still dwarfs that of anorexia; so it appears that the bedrock question―why must Western women go hungry―is one too dangerous to ask even in the face of a death toll such as this.

Rather than draw the correct conclusion that the number was probably wrong, Wolf instead uses it as part of an indictment of the Western world for supposedly not caring about women. Of course, that such a claim is implausible does not establish that it's false, since some implausible things are true. Instead, it means that the claim should be regarded as an unproven allegation until verified, especially when the advocate it comes from is someone with an ideological agenda, such as Wolf or Steinem.

This is a rare case of a bogus number where we seem to know the story of how it originated, as explained by Best:

Activists seeking to draw attention to the problem [of anorexia] estimated that 150,000 American women were anorexic, and noted that anorexia could lead to death. At some point, feminists began reporting that each year 150,000 women died from anorexia. (This was a considerable exaggeration; only about 70 deaths per year are attributed to anorexia.) This simple transformation―turning an estimate for the total number of anorexic women into the annual number of fatalities―produced a dramatic, memorable statistic.

It's also a good illustration of another point made by Best: "Once created, mutant statistics have a good chance of spreading and enduring." [Best's emphasis.] Here we are about twenty-five years after the statistic was first born, and over fifteen years since Sommers' debunking of it, and it still crops up in articles on the web. This is why you need to have a judicious skepticism about factual claims you see in the media, as well as the ability to check such claims yourself for plausibility.

Sources:

- Joel Best, Damned Lies and Statistics: Untangling Numbers from the Media, Politicians, and Activists (2001), pp. 63-64

- Christina Hoff Sommers, Who Stole Feminism?: How Women Have Betrayed Women (1994), pp. 11-12

- Gloria Steinem, Revolution from Within: A Book of Self-Esteem (1991), pp. 222 & 356

- Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty are Used Against Women (1991), pp. 181-182

Solution to "How many errors are there in this puzzle?": There's a grammatical error in the sentence―"is" instead of "are"―and a misspelling―"errers" instead of "errors"―which makes for only two errors.

Now, you probably spent some time searching for a third error, then gave up and concluded that there are only two. At that point, you may have realized that the sentence is false since it claims that there are three errors. However, if the sentence is false, that's a third error, after all!

You might've stopped there, thinking that you had found all three errors. But if there really are three errors then the sentence is true, in which case there are in fact only two errors. But if there are only two errors, then the sentence is false, in which case there are three errors, and the sentence is true… And so on, ad infinitum. You're like a computer program caught in an infinite loop!

So, what's the answer? How many mistakes are there? The answer is: there is no answer! The sentence is paradoxical. Note the self-reference, as in so many paradoxical sentences. Self-reference is a type of circular reference and sometimes―though by no means always or even often―creates a vicious circle.